-

Posts

8,149 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by allanyed

-

I understand the concern but consider there would be rope rails for the climber to hold on to while climbing up or descending the steps. A rolling ship, slippery steps, offset position, long coats and hanging swords, are a recipe for someone to wind up back in the bottom of the ship's boat or in the water. Allan

-

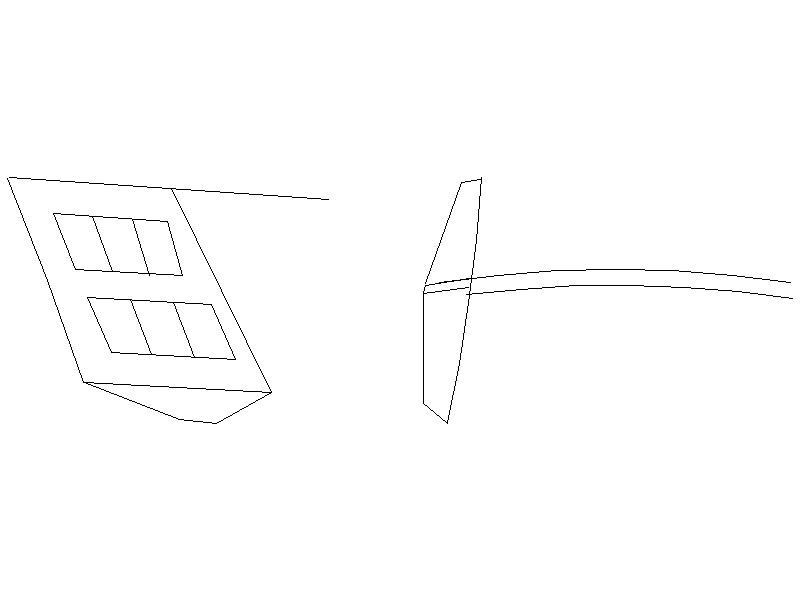

Ferit Assuming you mean dimension "A" in the sketch below, I checked a number of photos of contemporary models from NMM and Preble Hall and cannot find anything that indicates that the dimension "A" changes. It appears to be the same for every step on the photos I could study. None of the photos that I have are at a great angle to see this clearly though. I could not find anything specific in any books such as Goodwin et al, so I am only guessing, based on what I can see in the photos of the models. Allan

-

Druxey, I understand the comment of the stools but not sure about the quarter gallery. Is the attached simplified and exaggerated sketch what you are referencing? Thanks Allan

-

How very appropriate! Beautiful work as always. Allan

-

Every printer needs to be checked, including your home printer or even the ones at Kinko's and other architectural houses. I usually put a scale line or box on my drawings for this purpose to check at least the first few printed pages. Once you know the percentage adjustment, you can get that information entered before printing into the printer. A printing firm will know what to do, but at home, for small pages (8.5 X 11 or similar size), Acrobat works well for PDFs. There may be some free downloads that work as well as Acrobat, but I have never been able to find one. Would love to hear about any that are out there that are reliable. Allan

-

Gregory, In days of old, rope was given in circumference, never diameter. Move forward a couple hundred years and modern day suppliers use diameter. If you look at contemporary rigging tables, the dimensions will be the circumference, so beware if you are using them as a guide and order the rope diameter based on the circumference dimensions. You will have rope that is 3.14 times larger than it should be. Allan

-

Hi Dave, Welcome to MSW. Please tell us a little about yourself including where you are from. Regarding your question, I am not very familiar with French ships, but the Art of Ship Modeling by Bernard Frolich gives a little information on rigging for French vessels. Looking at the many model photos in this book, the standing rigging actually looks to be "un-tarred but he writes that, he uses two basic rigging colors in DMC cotton, dark (walnut) for standing rigging, and beige for running rigging. He does not differentiate for various years, but the book includes ships both before and after 1764. Your call in the end, but dark brown for standing rigging (not black) and tan for running should be OK. I defer to experts on rigging French vessels in this motley crew of ours at MSW. Allan

-

Keel to coils, superb!!! You set the bar higher than most of us can reach, but it will be fun (and frustrating) trying to do just that!! Allan

- 3,618 replies

-

- young america

- clipper

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Steel (1805) and the Shipbuilder's Repository (1788) list scantlings for a 16 gun cutter, 80'6" and 80' ( Length from the forepart of the stem at the height of the hawse holes to the aft part of the sternpost at the wing transom respectively.) Unfortunately there is nothing in either on cutters smaller than 16 guns. Allan

-

Kurt, I need to try the soaking idea next time I use the draw plate. My only concern is that if the bamboo swells when soaked in water, after being drawn through the plate, and then dries, it will be smaller diameter than intended. Not the end of the world and surely can be accommodated for if consistent. Have you seen this as an issue? Thanks Allan

-

For what it's worth, the tree nail cutter attachments were pretty limited in sizes. A good draw plate, including the one from Byrnes, allows anyone to make treenails to much smaller sizes than cutters. Too often we have all seen oversized treenails on otherwise super fine models and they appear to have the measles as a result. Bamboo strips and a draw plate will give anyone the capability of making all the sizes anyone could hope for. Bamboo will go to the tiniest diameter with very little effort and will be stronger than any other wood at those super small diameters. Bamboo skewers can be split several times then taken through the draw plate to make trennail stock. One package of skewers yield many thousands of treenails. If someone wants only the appearance of treenails, not the actual strengthening they give, it is far easier to just drill appropriate size holes and use a good wood filler in an appropriate color. Allan

-

Gregory, Longridge is indeed clear on belaying points for a first rate of the late 18th and early 19th century, but the types of rigging are extremely different than earlier periods so I assume (which is often a mistake) belaying points will vary, especially as there were no pin rails for much of the 18th century and earlier. Druxey, if I was closer to Annapolis and could spend week or so there taking photos and sketching lines to their belaying points, that would be a super project. I do have a lot of photos of many of the models there, but I never took any with the mindset of preparing rigging drawings. Maybe this would be a good project for Grant Walker and/or the model club that meets and works in their shop :>) Same could be said for someone in Paris or Holland et al to put together something on those nations. Allan

-

The biggest problem for me has always been finding specifics on belaying points. Anderson gives some written details and drawings as does Lees and a few others, but these are far from complete. Before the use of belaying pins, the information is even more scarce. If there is a source of definitive information on belaying points, I would love to see it. It would be great if someone had the time to trace rigging lines on various contemporary models and prepare a complete treatice and drawings on where all the lines are belayed for various rates, nations, and time periods. Allan

-

YT- I agree totally with your statement "never use Cyanoacrylate adhesive in scaled ship building for anything . Period. " CUDOS!!!! Allan

-

Ed, When you consider the planking thickness of the decks, the wales, the diminishing strakes, bottom planking, and rails (not to mention internal planking) there can be many different thicknesses. No matter how accurate the saw, the best investment I made to be able to have proper thickness of planks is a thickness sander. A good one such as the Byrnes will allow you to produce planks at a thickness within a few thousandths accuracy. I don't know that there would be so many different thicknesses for either the Morgan or Rattlesnake, but if there are, a thickness sander is a good solution to getting what you need. Allan

-

As she was only 320 days from launch on May 31, 1911 to her sinking April 15, 1912, and the fact that she was a luxury liner and no doubt extremely well maintained, I very much doubt weathering would be evident. Maybe some scrapes and bruises from docking and such, but weather related wear does not seem likely to me, except for some barnacle growth below the water line. Allan

-

Druxey probably knows as much or more about painting various materials than anyone here, but you may find this product interesting. It gets great reviews: https://www.amazon.com/Jacquard-Products-JAC1000-Secondary-Assorted/dp/B00A6WIW70?psc=1&SubscriptionId=AKIAINYWQL7SPW7D7JCA&tag=aboutcom02thesprucecrafts-20&linkCode=sp1&camp=2025&creative=165953&creativeASIN=B00A6WIW70&ascsubtag=2578201|nb432bcfd89e84e259a00e359946186f814 Allan

-

Cleaning Small parts prior to blackening

allanyed replied to src's topic in Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings

I agree that Sparex works extremely well. Soldering pastes, pickling materials, and other items for small metal work can be found in many places, but Contenti has been my go to place for a long time. The pickling powder can be had for $5 for a 2.5 pound bag that will last a lifetime in this hobby of ours. I am not involved with them in any way other than beng a happy customer. Allan -

Over all, the chart is a huge time saver, but always best to double check. It helped me find a couple errors that I made when preparing the mast and spar scantlings for Litchfield 1695. But be careful using the chart at http://modelshipworldforum.com/ship-model-rigging-and-sails.php as there are errors n the chart. For example, for a 4th rate between 1685 and 1699 it gives a length of the spritsail yard as 90 feet. According to Lees' Masting and Rigging for this period, the length should be 1/2 the length of the fore topmast, that is 90 feet divided by 2 = 45 feet. The sprit topsail yard is in turn 1/2 the length of the sprit sail yard, that is 22.5 feet, not 45 feet as shown on the chart. I suspect the length of the spritsail yard was taken as the same as the fore topmast by mistake rather than 1/2 the length. Also, the sprit topmast should be 17.8' long, not 12.6 feet using the Lees' calculation that it is 0.33 X the length of the main topmast for this time period. These may be the only errors in the entire data file but as always, check (measure) twice, cut once. Allan

-

I thought this would be an easy one to address but after speed reading appropriate sections in Seamanship Age of Sail by John Harland I found there was a lot to do in preparing and actually anchoring. In short, the anchor was dropped one at a time and the ship moved away from the anchor(s) with wind and tide until the anchor(s) bit. The number and selection of sails used when anchoring was depend on the wind conditions and direction. The hawser(s) was wrapped around the riding bitts a turn (sometimes twice) then secured once the ship pulled tight and anchor bit. I was unable to find any mention of using capstans or windlasses in anchoring. The number of anchors used could be as many as three or four, depending on wind and tide. There were different sequences used when coming to an anchorage head on with wind dead aft, coming in before the wind with the tide, coming in before the wind and against the tide, and anchoring on a lee shore, the last requiring as many as four anchors letting go first the weather sheet, then the weather bower, then the lee bower and last the lee sheet anchor. The helm was used at times to maintain the ship tight against the hawsers, and again there is no mention of using the capstans. There are about 28 pages on anchoring and mooring and there are numerous drawings showing the maneuvering in different situations in Harland's book. I am sure there are other members with more knowledge on this, but Harland is usually a reliable source of such information. Allan

-

Bazz A quick search and simple description shows that at the time of Trafalgar in 1805, Victory carried the following. Gundeck: Thirty Blomefield 32 pounders 9' 6" long barrel Middle gundeck: Twenty-eight 24 pounders 9' 6" long barrel Upper gundeck: Thirty 12 pounders 8' 6" long barrel Quarterdeck: Twelve 12 pounder 8' 6" long barrel Forecastle: Two 12 pounders 9' long barreland + Two 68 pounder carronade 5' 2" long barrel The carriages of the 24 and 32 pounders would be 72" long but the carriages of the 12 pounders approximately 67" long. Scaling down, the 32 pounder carriages would be 19mm long and the 12 pounders 17.7mm long. The carronade mountings are of course a different design altogether. Allan

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.