-

Posts

13,355 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by druxey

-

HMS Naiad 1797 by albert - FINISHED - 1/48

druxey replied to albert's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1751 - 1800

Superb work, Albert. Keep those progress photos coming! -

Three strakes a side completed now. Rubber bands and small soldering clips make fine hold-downs while roughly shaped planks are drying out.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you, Mark! Jim: the strength of the assembly at this stage is surprising, even though the individual parts are so flimsy. If the planks are cut accurately so that there is no stress in the hull, it will not distort. In past experience, sometimes the breadth will expand slightly when the shell is complete, but this is easily corrected when the internal elements are added, producing a very strong model indeed. The barge I'm modelling is not the Prince Frederick's one in Mark's photos: this one, while similar, has far less carved work. However, it will be a lot of fun to do when I get there!

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Nice details, Mark. Thank you. The carved works are wonderfully executed. The rowing benches on these barges do have a central element to them. The items I'm particularly interested in are the standards supporting the ends of the thwarts and whether there are also supporting standards above the transom. These cannot be seen on the usual photographs of the barge.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

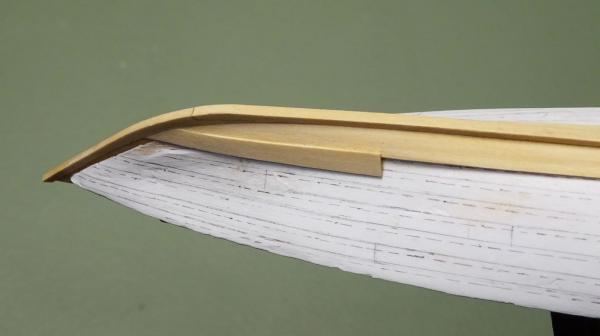

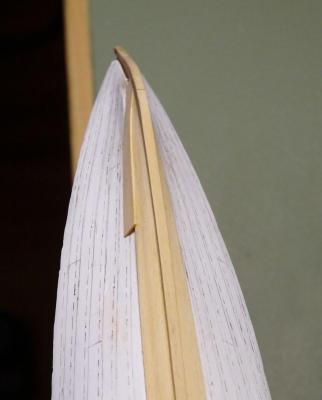

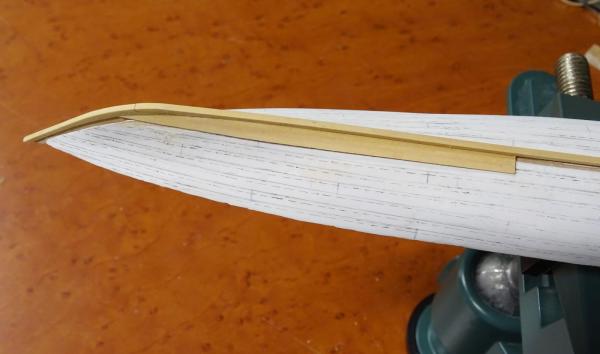

The second strake is in on the port side. One can see the gain at the bow and stern, as well as how the boat keeps its shape when taken off the plug. From here on it is simply a matter of spiling and shaping each plank as I work up (down!) to the sheer strake. All one need do is make sure to conform to the mark-out on the plug.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Frégate d'18 par Sané , la Cornélie

druxey replied to JohnE's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Only switch from x if there is compelling and overwhelming evidence from y! That set of lines looks very nice, John. -

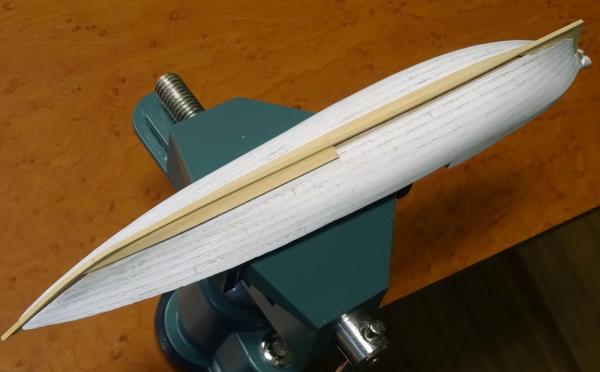

Mark: if you have detail photos of the interior of the forward part of that vessel and near the tiller, posting those would be very helpful. Thanks for the kind offer. Yes, these crafts were very lightly built but surprisingly strong. Think of them as predecessors of today's 'eights' rowing shells. These two photos show how the lap disappears into the rabbet at the bow. The second strake also has a rolling bevel that fits the one on the edge of the first strake. You can also see that there is no gap along the lap, as the bevel that was sanded in takes care if this. PVA glue was applied with a very small brush and any excess cleaned up immediately.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

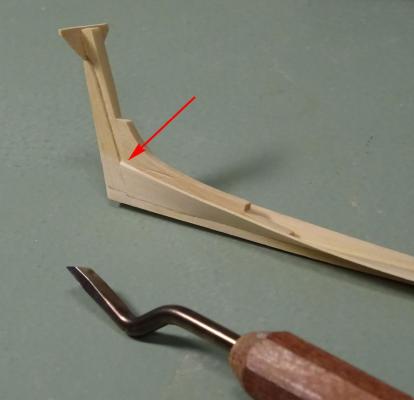

Here are a couple of photographs of the land - the bevel - being sanded on the edge of the garboard and of the gain at the end of the rabbet (arrowed). The gain is basically a rolling bevel. It ends at 45 degrees so that the next plank will come in flush at the rabbet. Essentially clinker becomes carvel over the last 9" or 12" of the strake.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Great stuff, Glenn! The original designer of these flywheels was very ingenious. To reproduce these in miniature you also had to be!

-

As Oscar Wilde said, "You will, you will," Michael!

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

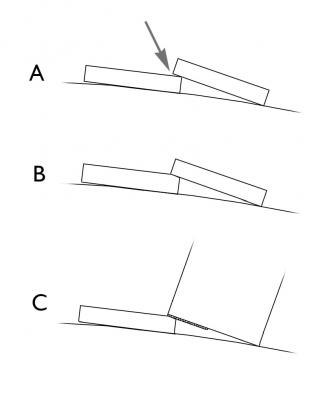

A little more time was spent on completing the starboard garboard strake. The next step is to shape the lands for the second strake of planking. If one were to omit this step, the second strake would not have any gluing surface and there would be a gap under the strake, A. Obviously, a bevel is required. It varies in angle along the strake according to hull curvature, B. To cut this accurately, I took some scrap wood the width of a strake and rubber cemented some 220 grit sandpaper along one edge, C. Keeping the 'safe' corner of this along the mark-out of the second strake's far edge, it is easy to shape the correct bevel along the installed strake. The next instalment will show this completed. A note: I found the short pins under the keel not very effective in holding the keel straight, as the keel kept popping off. On a another long narrow hull I would drill the pins all the way through the keel. A digression: One side effect of modelling an open boat at this small scale is the amount of wood required to build it. Very little is needed, making this a very economic exercise in materials, but not in time.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Michael: I cut the stock several thou over-thick on a Byrnes saw with a micrometer adjustable fence. I then process it through his thickness sander to within .004" of finished dimension. A fine sanding block removes sanding marks and completes the prepared stock. The leaves I'm using are just under ¾" wide. George: gesso is the (usually) white compound artists use to prime canvases. These days it has an acrylic base. Once dry, one can sand it to a very smooth surface. Any reputable art store will carry gesso. (The word is pronounced with a hard 'g', as in 'jesso' - or 'George'!) Thanks again for the 'likes', folks.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

THE 74-GUN SHIP by Jeronimo

druxey replied to Jeronimo's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1751 - 1800

Exemplary work, Karl!- 194 replies

-

Surprisingly little pigment powder is required to color glue. I prefer to mix a small amount of pigment into paste with water before mixing with white glue. As Ed says, the mix will dry much darker than the liquid glue. Please wear respiratory protection as the pigment powder is very fine and easily becomes airborne.

-

Frankie: lead deteriorates at a rate dependent on the atmosphere and temperature it's exposed to. I've seen lead 'fuzz' in comparatively recent models and still undeteriorated lead in older models. Either way, it's toxic stuff and needs to be handled and disposed of appropriately. I've currently got a model for conservation with about 70-year old corroded lead cell batteries in it. They (and the lead-based paint that's flaking off) go to the hazardous waste disposal site.

-

Further progress. The garboard is in on the port side and the forward plank on the starboard. The interesting thing is that, at any point in planking, provided one has spiled and shaped the plank to lie without stress, one can remove the model from the plug and it will retain its shape.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Joel: stay with this log and all will be revealed! In short, the laps will be bevelled in a while and gains cut at bow and stern. It will be done just as in full-size practice, but considerably smaller.

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you, gentlemen all. Finally had some quality time on the model. The first garboard plank is now spiled, cut, shaped and fitted. The stock is thin enough to cut with a sharp scalpel blade. The twist was achieved by cold wet bending and holding in place using rubber bands until dry. Castello takes more persuasion to bend than holly. Once the plank was dry, it was glued in place. I needed to cut back the plug more at the bow to allow the plank to land nicely in the bow rabbet. One plank down, many more to go!

- 641 replies

-

- greenwich hospital

- barge

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

A two year old? What were they thinking???? Anyway, both models are a good restoration challenge and I'm looking forward to seeing them returned to their former glory. Good luck with them.

-

White Paint Issues

druxey replied to rynmss's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

And is the paint well stirred? In some paints the pigment tends to settle out fairly quickly.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.